The Shape of Erddig

Erddig Hall, North Wales

A Christmas Visit to Erddig

Yesterday I called in to Erddig, a National Trust property near Wrexham, North Wales. I love visiting houses over Christmas and seeing how they’ve made the rooms all cosy and festive. The house didn’t have electricity until the Trust took it over in the 1970s, so the interior was presented as it was before that time – well, almost! There were Christmas trees with fairy lights, and the candles were the battery type.

Unusually for a stately home, you enter through the servants' quarters and are greeted by photos of the servants on the walls (see History section). Kitchens are always some of my favourite rooms, and this one was laid out with festive food on the tables. I don’t have many photos of the inside as it was so dark that when I got home, I found most of my pictures were just a blur of light!

A Winter Garden Awakening

Actually though, I spent over an hour in the garden before even going into the house. As I wandered around, glad to stretch my legs after a couple of hours in the car, I was thinking “Hm, not much winter colour here.” So, I had to change my perspective – “What is here then?” And then I realised – Erddig in winter is all about shape. Textures and patterns are also important, but the predominant feature is shape.

I like visiting gardens in winter because you get to see the structure and bones of a garden before it’s taken over by plants and your eyes are madly dashing from colour to colour. Once I had changed my perspective, I realised that Erddig is a superb garden in winter. When you walk around looking for shapes, patterns, and texture, you realise there is an abundance of all of those things.

It got me thinking about how easy it is to dismiss something because it isn’t presenting what you expect to see. What it had to offer was in plain sight, but I just didn’t notice it until I was partway around the garden and was actually thinking about it. And then, it was everywhere.

The Historical Significance of Erddig's Garden

By the time I had finished my second walk around and was heading into the house, I discovered the information board – and then it all made sense! Erddig is described as having “one of the most important formal gardens in Wales and, arguably, in Britain.” The garden is an extremely rare survivor and a unique illustration of the influence of Dutch and French garden design.

This is why it struck me as unusual. Very few gardens from this period exist in this country. The landscape movement of the 18th century, epitomised by the work of Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown, swept away hundreds, if not thousands, of formal gardens and replaced them with ‘naturalistic’ style landscapes rather than gardens. Somehow, the formal garden here survived when William Emes, a contemporary of Brown, landscaped the property in the 1770s. He kept the walled garden and the formal design whilst landscaping the parkland.

The Legacy of the Yorke Family

Erddig was in the ownership of the same family, the Yorkes, for nearly 250 years, and they introduced many new features to the garden. Places to walk – the Yew Walk, Holly Walk, Moss Walk, alongside a Parterre and Rose Garden. They also planted many trees, particularly conifers of all types and sizes.

Sadly, in the early years of the 20th century, Erddig went into decline, and the garden became overgrown. The last owner, Philip Yorke III, gave the estate to the National Trust in 1973, who then spent four years restoring the garden. At the time, it was the largest project they had ever undertaken.

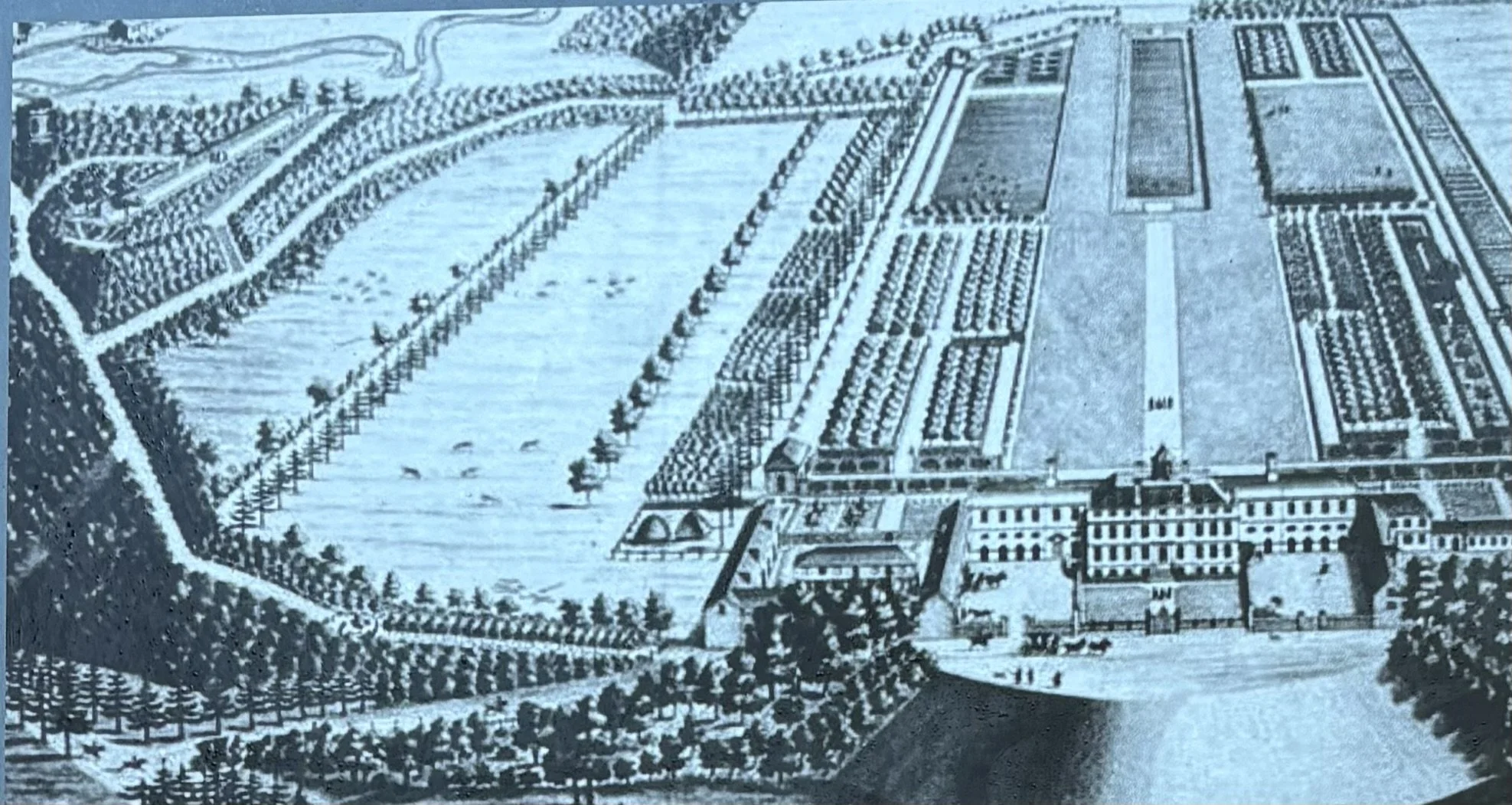

The engraving I have copied from the information board shows “Badeslade’s bird’s eye view of Erddig, 1740.”

Look through the gallery and see how many different shapes you can spot! Then read on below for the History of Erddig.

Badeslade’s bird’s eye view of Erddig, 1740

History

Early Days

This area of land near Wrexham in North-east Wales has been built on since the 8th century. Running through the parkland of Erddig Hall is Wat’s Dyke, the lesser-known cousin to Offa’s Dyke. It was probably built as a boundary marker between two rival kingdoms - that of Mercia and Powys. There is a natural escarpment above the River Clywedog on which a Norman motte and bailey castle was built (nothing remains) but the story of Erddig really begins in the late 17th century.

Building the Hall

The title of High Sheriff of Denbighshire is a prestigious one - and it needs an impressive residence to go with it. So when Joshua Edisbury was appointed in 1682 he gave the task of designing and building a new house for himself to Thomas Webb. Unfortunately the prestige didn’t come with the necessary means and Edisbury soon ran out of money. He had embarked on an impressive house 9 bays wide and had to take out loans to fund it.

He approached the East India Company and his friend Elihu Yale for money. Both gifts and money were exchanged - including ale and chutney! However, his benefactor Yale had to call in his debts and, despite, being a friend, demanded 100% interest!

By 1709 Edisbury was bankrupt and forced to sell Erddig Hall unfinished.

John Mellor, a London lawyer bought both the debts and the Hall. He added wings to both sides and was helped by his nephew Simon Yorke to whom he left the house on his death in 1733.

Continuity of the Yorke family

From that point until 1973 Erddig was in the Yorke family - 240 years. Each owner was called either Simon or Philip.

Simon’s son Philip received and inheritance which enabled him to marry well and the couple were able to make improvements and build a new kitchen, offices and stable yard.

Their son Simon II married Margaret Holland and they installed underfloor heating and the bell system. It was their son Simon III who recreated the gardens and park during the 19th century.

In 1922 Simon IV inherited at age 19. Like so many great houses after WWI, decline had begun and there were few servants to maintain either the house or garden. When the Coal Board was nationalised in 1947 coal was mined from under the house, resulting in serious subsidence.

Throughout the 20th century Erddig remained without electricity or telephone. Simon IV became a recluse, never marrying or wanting to change anything about the house.

On his brother Simon’s death, Philip III inherited an estate that was in serious decline. He was also unmarried so there were no heirs to take on the property after his death. As a result of this Philip negotiated with the National Trust for them to take it on in 1973.

The National Trust Restoration

A four-year restoration project began which Philip lived long enough to see, dying in 1978. The agreement that Philip had with the Trust meant that every item at Erddig had to remain there. All 30,000 objects! Nothing had been thrown away for decades, and in some cases hundreds of years. This is why Erddig is also an accredited museum.

Collections

One of the unique collections is the series of portraits of the Yorke family servants. When you enter the house you begin in the servants’ quarters where you see the walls covered with paintings and photographs of the people who worked there. Philip I commissioned the first set of 6 portraits in 1791 and this began a tradition which continued for almost 200 years.

The Servants

The ages of some of the staff are particularly interesting:

A house-maid of 87!

Kitchen man of 71

Carpenter of 73

Firstly, this shows that people were living long lives and were healthy enough to work but also that the family kept them on, probably on light duties but nevertheless, it made them feel useful and valuable.

Not only were the servants either painted or photographed but poems were also written about them! That has to be a first surely?! Clearly the Yorke family were dedicated to the house and garden and this extended to all the people who made it their home or workplace. Generations of the same families continued to serve the Yorkes and work “at the big house”. This was despite the fact that the family were never particularly well-off and are unlikely to have paid the highest wages.

However, it wasn’t all roses in the family/servant relationship department. In the early 20th century the new Mrs Yorke loved entertaining much more than keeping household accounts. That job then fell to the Cook-Housekeeper Ellen Penketh. The accounts were in such a poor state that Mrs Yorke accused Ellen of stealing and took her to court for theft. Ellen was found not guilty by the jury - but it isn’t clear whether she continued working at Erddig after that.

The Garden

Erddig is famous for its apple trees - 180 varieties which were part of the original plans of Joshua Edisbury. Beautifully trained and pruned they are particularly striking in winter. Even more so are the avenues of pleached limes which stretch out down the garden. They have to be pruned by hand with the branches connected together. This would take 10 weeks for one gardener to do on their own.

The Parkland

The estate still contains 1200 acres of grassland, woods and rivers. Most of the ‘landscaping’ of this land took place in the 1770s under William Emes, landscape designer. He was asked to not only make the parkland look good but also to reduce flooding of the Afon Clwedog which runs through the estate.

Emes diverted the river to make canals, ponds, lakes, weirs and waterfalls - all of which are still visible today. He also used the existing features of Wat’s Dyke and the Norman castle and planted avenues of trees to highlight them. The two rivers that run through the estate still have fish, eels, water voles and even otters. And of course, water brings an abundance of birds, mammals and insects so that the whole estate is rich in wildlife at all times of the year.

This history section is summarised from the National Trust guidebook. Click here for the NT Erddig website if you would like more information or want to visit. It’s open more or less all year and has the usual NT cafe and shop facilities. Plus an excellent second-hand bookshop (where I spent far too much money…..)